by Simon Wegerif

by Simon Wegerif

Who, why and what?

The whole principle of monitoring Heart Rate Variability (HRV) as an athlete is that you can see the impact of individual workouts and cumulative loading on your recovery. It stands to reason that the longer lasting and more intensive the workout, the longer it will take to recover. But what exactly is the relation between workout intensity and recovery? Is this a linear model where recovery time increases with power, speed or heart rate? Are there some threshold effects where the training load perceived by the body changes significantly?

Norwegian researchers, led by well-respected endurance sports scientist Stephen Seiler decided to look more closely at the effects of intensity and duration on HRV recovery.

Experienced runners and orienteers were separated into trained and highly trained groups. They used 1-2 hour sessions of training with intensity controlled to remain below the individual first ventilatory (first lactate) threshold as well as high intensity interval sessions.

What did they find?

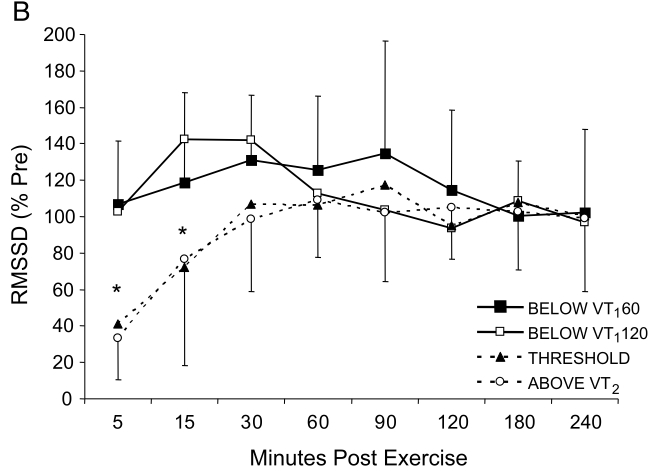

Where the intensity level was controlled to below threshold, HRV values were already recovered to pre-exercise levels within 5 minutes of ceasing exercise (see chart below). The duration (either 1 or 2 hours) did not alter this, although there was a tendency towards rebound to levels above pre-exercise values for the 120 minute sessions. Conversely, both the threshold, and very high intensity exercise caused significant delays in recovery of parasympathetic HRV.

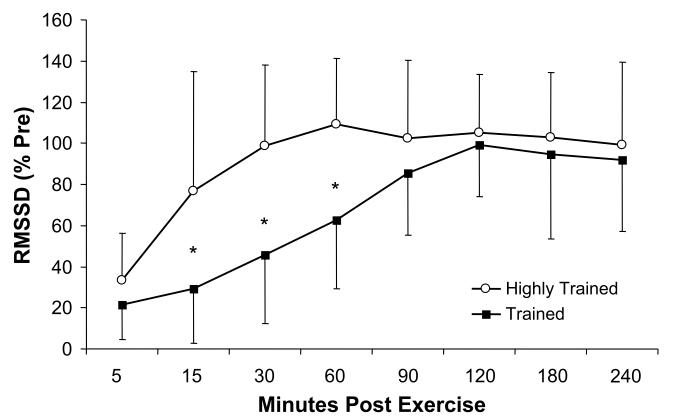

The researchers were also interested to see whether the parasympathetic HRV reactivation was different between the highly trained and trained subjects. The chart below shows that HRV recovery was delayed in the less trained subjects by 60-90 minutes compared to the highly trained athletes.

Layman’s lowdown

The authors concluded three key findings:

1. There is an increase in autonomic stress (as evidenced by delayed HRV recovery) once the first ventilatory (lactate) threshold was exceeded. Therefore, this threshold seems to be a clear boundary for ANS disturbance, i.e. workouts below the level have little impact on HRV recovery, whereas intensity levels above impact HRV recovery.

2. There appeared to be no additional delay for HRV recovery when working at an intensity level of 95% VO2max compared with training at lactate threshold intensity.

3. More moderately trained subjects required 2-3 times longer to reach the same level of parasympathetic recovery as highly trained subjects.

The conclusions I personally took from this study are:

1. You should be able to train for long periods of time below the first lactate threshold without causing HRV to be negatively disturbed. Therefore you can continue to do this kind of base training day after day without stressing the cardiovascular system. Perhaps this is how world class endurance athletes manage such high training volumes.

2. Do your intervals very hard rather than moderately hard, because it won’t make a difference to your recovery.

3. If you are not a naturally gifted or highly trained athlete with a VO2max of 70+ ml/kg/min it will take you (much) longer to recover from a hard session.

As usual, we would be interested to hear from ithlete users who have personal experience to either back up or dispute these findings!

Have to say that the Layman’s lowdown was not so ‘lay’

My take is:

If you go easy you can keep doing it a long time without tiring yourself. You’ll recover easily and you can keep doing it over the longer term, without hurting yourself.

If you push it hard for too long, you’re going to get knackered really quickly and it’ll take you a long time to recover from that effort. Plus if you keep doing it, then you’re going to get really tired and potentially damage yourself (overtrained).

Doesn’t seem to say anything about long term performance improvement though?

Other thing is that with IThlete you recommend to measure HRV first thing in the morning – once a day. But in this trial they are measuring it just before and just after the activity. I am right? If so Are you thinking of making a version of iThlete that supports this kind of measurement?

Hi Mathew,

Good points. I’m finishing off a blog post right now to try and address your points about optimising long term benefit based on a new study that’s just come out.

For the last point – you can do as many measurements as you like during the day. Only the first one is shown on the Chart summary screen, but they are all saved in the Edit view, and you can see the additional readings when you rotate the Chart to landscape view (iOS devices only at present). I quite often take readings a few mins after training sessions, and they can be quite insightful.

Thanks for a very interesting and helpful article. Have you any thoughts on what implication does this have for structuring sessions. for example could it be best to do the intensive session at the end of a number of days training then have a rest/ recovery day… Or have the intensive session after the rest/ recovery day when the athlete is recovered and then do the lower intensity sessions?

Thanks for the comment Paddy. There is research to underpin the idea that it’s best to do HIIT when the athlete is well recovered. Not only are they more likely to maintain the required concentration & effort, but new thinking on periodisation (Kiely) suggests that adaptation will be better. ithlete Pro recommends HIIT / intensive sessions when both recovery and activation (sympathetic) levels are above normal.