Introduction

Researchers Jamie Stanley & Jonathan Peake from the University of Queensland, with the guidance of heart rate variability (HRV) sports research supremo Martin Buchheit have put together an important review article with over 120 references. The paper takes a critical look at the research and the many studies on HRV following exercise with the objective of extracting the clearest possible recommendations on how to use HRV to maximize the effectiveness of periodised training. They focused on endurance sports because there simply aren’t enough studies on strength & power sports to come to clear conclusions yet (more studies please!).

What did they do?

They reviewed studies on HRV and exercise in two separate sections:

1) They performed detailed quantitative analysis on 8 studies that provided sufficiently complete data to analyse changes in HRV in the immediate 90 minutes following single exercise sessions at different intensities and also the subsequent 48 hour recovery period. Studies that did not include pre-exercise or baseline data were excluded. When choosing from multiple HRV parameters, they used LnRMSSD (the ithlete measure) wherever possible for reliability reasons.

The intensity level of exercise performed was categorized using a 3-zone model, (like the Lucia TRIMP) which distinguishes between exercise below first ventilatory/lactate threshold (Z1), exercise above the second ventilatory/lactate threshold (Z3) and the region between the two thresholds (Z2). The selected studies were of similar length in time however, making it difficult to categorise data on the basis of duration.

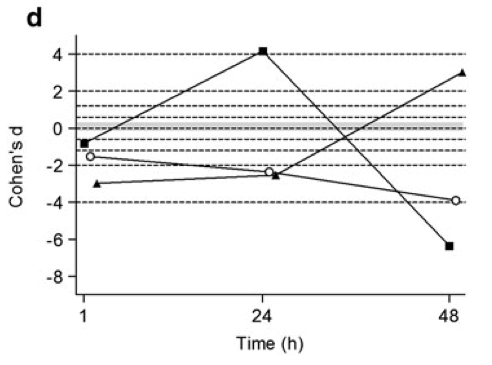

The output of the analyses was charts that showed not only the time course of HRV itself, but even more importantly, the standardised differences between pre and post exercise changes at different points in time. These effect sizes were expressed using Cohen’s d parameter, which basically makes it easy to understand the average magnitude of an effect in the presence of variations between individuals. A value close to zero represents a trivial change, a value around ±1 represents a large effect, ±2 or more a very large effect.

2) They examined studies of HRV and extreme exercise – a 46 km trail run at altitude, a 75 km x-country ski race and that hardy perennial of extreme exercise, the Ironman triathlon.

What did they find?

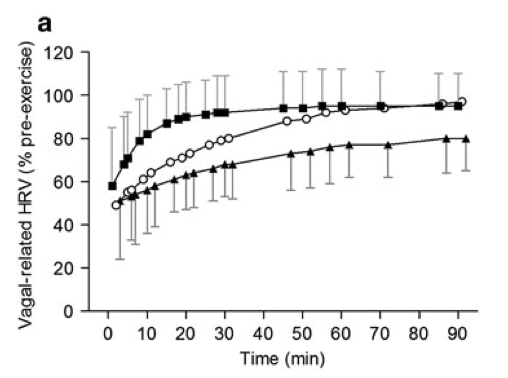

1) Analysing the immediate period following exercise at different intensities they found an intensity dependent effect. The highest intensity showed the slowest recovery, but in no case was HRV back to pre-exercise levels by the end of the 90 minutes. The chart below shows this short term recover for low intensity (squares), threshold (circles) and high intensity (triangles):

What is even more interesting is what they found looking at the effect of intensity on the 24 – 48 hour intermediate recovery period as shown in the following chart.

What is even more interesting is what they found looking at the effect of intensity on the 24 – 48 hour intermediate recovery period as shown in the following chart.

There is a very large rebound effect on HRV 24 hours after low intensity exercise (squares). This is followed by an equally striking reduction within 48 hours.

There is a very large rebound effect on HRV 24 hours after low intensity exercise (squares). This is followed by an equally striking reduction within 48 hours.

- This situation is mirrored for high intensity exercise, where the rebound occurs after 48 hours, following a period where HRV is depressed.

- For threshold intensity training (circles), HRV remains depressed during this 48 hour period.

2) The analysis of the extreme events revealed some additional insights:

i) HRV in the last few days before major competition was reduced, possibly because of either effects of tapering, and/or pre-event nerves.

ii) HRV returned to baseline within approximately 24 hours, suggesting that for low intensity (i.e. fully aerobic) exercise, the duration is not the determining factor for at least this aspect of recovery

What does it mean?

Linking the timing of HRV rebound to the intensity of exercise has some far reaching implications for structuring individually periodised training programs.

In particular, if the HRV rebound does really signify supercompensation (as the authors argue), then these periods are likely the optimum time to train for greatest performance gain.

The authors go on to discuss how to compose a periodised endurance programme based on these principles that we may summarise in a future post, but overall this review is an important step forward in using HRV to guide endurance training not only to avoid overtraining but to maximize performance gains.

Original article

Sports Med DOI 10.1007/s40279-013-0083-4

Cardiac Parasympathetic Reactivation Following Exercise: Implications for Training Prescription. Jamie Stanley, Jonathan M. Peake & Martin Buchheit. Springer International Publishing Switzerland 2013

I would be interested to know what they suggest for multi-day mountainbike races. Is it best to pace throughout the event, which could be anything from two days to nine, or to increase intensity each day.

Recovery is an essential factor in stage racing and yes, one can control nutrition and rest, but where does intensity fit in?

Many thanks

Hi Sonja,

That’s a good, but quite specific question, and this paper does not provide a recipe for multi day competition – only for training & adaptation effectiveness.

The paper summarised in this earlier blog post http://myithlete.com/blog/?p=96#.U2td7a2wKDw did look at HRV during a Grand Tour, and noted that HRV from at least one hard working domestique crashed some time between days 9 & 15.

Personally, I think that if you know your VT1 heart rate (or power) accurately then you can manage the recovery load, since this is quite an abrupt intensity threshold: recovery within 24 hrs if you keep below, over 24 hrs if you go above. Duration seems to have only a minor role compared with intensity.

Bottom line – if you can manage to keep competitive for the first few days whilst operating just below VT1 then you can progressively build the pace in later stages, confident that some of your competitors are likely to be less recovered.

I’m not a coach though and would like to hear other opinions.

Thanks for the excellent Summary!!

One thing I would add is that the HRV positions studied in this paper were either supine or seated. It has been my experience that standing HRV seems to often react differently in the days following strenuous workouts when compared supine or seated HRV. I think this would make for a very interesting follow-up as I am only an N of 1. The stage of training period (base, overload, taper) may also play an important role in interpretation and this is where I think weekly averages may be illuminating. Such a ripe feild for improved understanding, very exciting.

Hi Seth

Fully agree that this is an exciting paper – all the more because it is a meta study review. I’m still trying to make up my mind about position, and think that sitting might be an acceptable compromise involving some orthostatic stress to reduce vagal saturation effects, whilst still being comfortable & relaxed.

Weekly averages are definitely good to look at, and we have had Weekly & Monthly change indicators right from the start, using colour codes derived from deliberate overload studies (ouch!).

Hi Simon,

I myself don’t find it especially burdensome to capture data in multiple positions. At rest collection what I call supine is actually a reclined position like a lawn chair. I gues that would be between flat supine and sitting. My HRV is considerably more stable in that position as compared to standing. The question for me is whether the extra variability when standing is signal or noise. Higher measurement variability is only a bad thing if it is random noise. If instead it reflects higher sensitivity to prior training or exercise readiness then it might reveal useful patterns. I saw one study where it was suggested that variability in the variability (HRV) was a good indication in an elite triathlete. Sitting HRV as a compromise position (no pun intended) is interesting. I tend not to collect in that position.

Many thanks again for your helpful comments.

Hi Seth

The example data featured at the bottom of this page

http://www.ilog.ca/help/Rusko_Heart_Rate_Test.htm

certainly shows more variability in the standing position, and the resulting variation is not considered by the author to be noise. I do my HRV standing, and like you, do wonder about the significance of this variability, though I have to say that over 5 ys daily use, the ithlete colour codes based on Smallest Worthwhile Change have been outstandingly helpful.

Hi Simon,

Many thanks again – I had seen a few studies that looked at orthostatic challenge during the act of standing as well as in the standing period where HR becomes stable. I was not familiar however with the Rusko test so I very much appreciate that interesting link. I actually dropped my IPAD breaking the Ithlete receiver two days ago so I am finishing out my marathon cycle by recording HRV with my Suunto T6. So the last few days I have been following a similar protocol to the Rusko test looking at a curve like the one presented in the link. Your timing is impeccable — Thanks again!

“There is a very large rebound effect on HRV 24 hours after low intensity exercise (squares). This is followed by an equally striking reduction within 48 hours.”Why/would/your/fitness/decline/below/base/line/2/days/after/a/training/session.its/not/consistent/with/detraining/literature/i/have/read?

Hi Rich. I don’t think this 48hr reduction indicates detraining, more likely a compensation following the increase in plasma volume (first stage of adaptation) that occurred within 24 hrs of the low intensity training. I’m not sure this phenomenon is fully understood yet, but the findings of this high quality study indicate that it is seen consistently.

Thanks for this article. It at least tells me that rebounds after a hard workout (running) seem to be normal. Frequently my HRV increases by 20+points the day after or two days (after a workout). It may then drop below baseline. It doesnt quite seem to be so neatly ordered around the type of workout as this study but the study at least tells me that super compensation occurs.. I like to watch my stress levels and I was concerned this indicated I was stressing by body too much.

I pay good attention to the weekly/monthly changes.

Im not totally convinces about the authors idea that the time of super compensation is the best time to train. Need more evidence on this .. Thanks again!

I am a 68 year old athlete who has run most of my life. Today I went to the track and did 13 laps with a 51 seconds sprints for the 220 and jog slowly the other 220. I felt fine now that I was resting at home I checked my HRV and it was 235.

What does that mean? My sleeping HRV overnight was 73.

Hi Jerry,

It sounds like you are using another program to measure your HRV as that would be an extremely unusual score on the ithlete scale (and we don’t track nighttime HRV). If you have some ithlete data I’d be happy to take a look and see if we can add some additional value.

Best, Laura