by Charlie Hoolihan, CSCS

A member of my training group just finished his first Ironman™ in 12:31 (1:18 swim, 5:51 bike and 4:59 on run) and his training was unique for an event this long. His program schedule may be of interest mainly because it was based on a much higher percentage of short session, high-intensity cardiovascular intervals combined with heavy strength training. Not only did this design take less time per week than most programs, the running portion of the program rarely exceeded 20 miles per week. Despite this low mileage, he was able to run steadily the entire marathon.

A member of my training group just finished his first Ironman™ in 12:31 (1:18 swim, 5:51 bike and 4:59 on run) and his training was unique for an event this long. His program schedule may be of interest mainly because it was based on a much higher percentage of short session, high-intensity cardiovascular intervals combined with heavy strength training. Not only did this design take less time per week than most programs, the running portion of the program rarely exceeded 20 miles per week. Despite this low mileage, he was able to run steadily the entire marathon.

To begin with

A few caveats must be disclosed…

First, the primary reason for his success and improvement was his commitment to six days per week of training which he had never done previously.

Second, a primary goal of “finishing an Ironman” gave the program a lot more flexibility to experiment with this new approach. An experienced athlete with a goal of finishing an Ironman in under 11, 10 or 9 hours would be a different matter.

And finally, this style of training is not for everyone. Genetics play an important role and he was of strong Celtic/Viking stock. This enabled an educated guess he would be more physically suited for a higher percentage of fast-twitch muscle fiber training. Plus the fact he had few Kenyan features was another tip-off.

Goals

There were several goals involved in determining our course of action. First and foremost, was the goal of finishing an Ironman distance.

With this goal in mind, the training also needed to be set up around the schedule of a Fortune 500 executive and as well as his family life. Given these additional factors, establishing training around higher intensity training with a smaller time commitment was an important goal.

The Plan

A schedule calling for high demand training for six days per week for two weeks followed by low intensity workouts for one week established our undulating periodization structure. During the early mornings, weekday workouts were between 60 and 90 minutes and always done with at least two of the triathlon segments. These workouts contained Zone 4/5 high intensity cycling, stair climbing and running intervals, strength training and resisted running.

There was finally only one long distance day set on the weekend as well as one off day. This is somewhat different from most plans but it enabled him to have one weekend day to spend with family as per the original goals.

Another unique aspect of this weekend distance workout was they were mostly some form of bike/run workout. One weekend it would be long bike/short run (i.e. 180 min/30 min) the next short bike/long run (40 min/160 min) and the third was a triathlon time-proportion 60% bike/40% run (120 min/90min).

To help insure he avoided overtraining, he monitored his daily ithlete Heart Rate Variability (HRV) which was strong even during the higher intensity bi-weekly phases. There were steady declines in HRV scores over the two weeks of high loading but they never entered into what we would consider negative indicators. He usually bounced back to higher or baseline HRV after the off week so these indicators were a positive sign of the direction of the training. The ithlete HRV feedback was critical in helping us through this type of training.

Breakdown of training load during HIT weekdays

- Baseline peak measurements for swimming, running, indoor cycling and on a stair climbing machine were set via 30 minute threshold tests which we called Endurance Threshold or ET. From here we were able to work off of peak heart rates in each modality and therefore create high demands no matter what combination of workout was set.

- Because he was good swimmer, we mostly limited his swimming during the build-up period to twice per week for 30-45 minutes of high intensity intervals. As race day neared, one of the training sessions became an hour long swim to psychologically prepare for the distance.

- During the week, two to three cycling workouts of with 30 to 40 minutes of high intensity intervals ranging from 3 to 8 minutes long were primary components of the workout. There were also two days of weight training with a day for anterior cycling muscle group emphasis and a day for posterior running muscle group emphasis.

On the cycling weight training day, we set up indoor cycling bikes in the weight room and performed a six to eight exercise circuit followed by a three to five minute zone 5 interval. On the run weight training day, we followed up the circuit with running sections with resisted tire pulling for quarter to half mile runs. We typically got in around three circuits in an hour.

- The resisted running helped develop posterior leg muscles and were effective in helping convert strength training to run specific training. Un-resisted runs also followed each tire pull. An example of the run circuit would be strength exercises – deadlifts, lateral band walks, single leg dead lifts, hip thrust, single leg hip thrust, calve raises, single leg calve raises and glute ham raises followed by half mile tire pull and half mile run.

On cycling strength days, HIT intervals followed each weight circuit to accomplish a similar transfer of muscle stimulus. A 30 to 40 minute cycling session started the workout and an example of the circuit was squats, step ups, Bulgarian split squats, kettlebell swings and banded wall sits followed by a 5 minute peak effort cycling

- Stair climbing intervals followed by treadmill running was also a staple mainly because the stair climber is a good run stimuli without the pounding 5 to 7 times body weight on the joints. The primary duration during these sessions came from the stairs and a short follow-up on the treadmill.

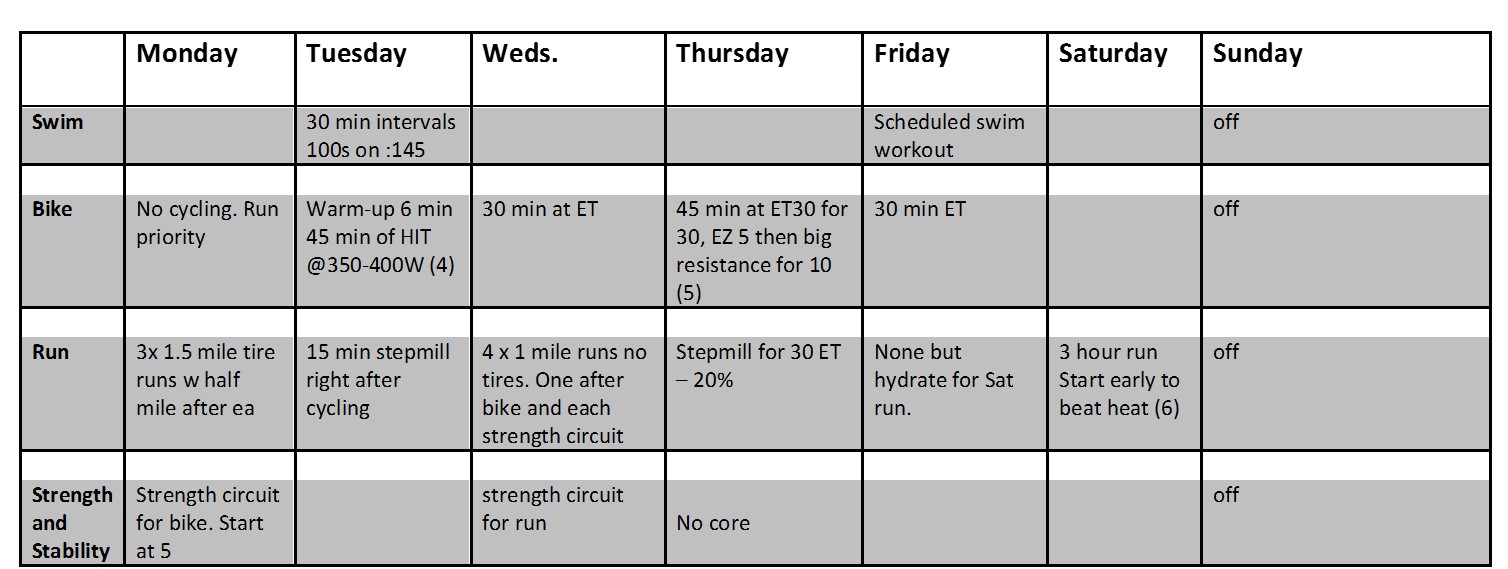

Below is a grid indicated a breakdown of a typical high load week. We were trying to emphasize running a bit more so this one was about a 26 mile week for him.

Conclusion

“In the absence of time, intensity is the key to performance” Chris Carmichael

Basing the training for an event lasting 10 or more hours on short distance high intensity workouts seems counterintuitive but the research over the past 15 years has indicated significant aerobic improvements with sprint and strength style workouts.

It was unknown territory with Ironman distance triathlons but books such as Chris Carmichael’s Time Crunched Cyclist and Pierce, Moss and Scott’s Run Less, Run Faster provided documented successful programs for sub 5 hour Century’s and sub three hour marathon’s respectively.

While we didn’t follow any particular program closely and probably ran our run/stepmill intervals harder and more frequently, the information provided in more than 9 books and 14 scholarly articles used in my Enduring Intensity article provided a lot of smaller elements.

The most exciting aspect is that it worked and worked well. His preliminary time goal was 13:30 and he was faster in each segment of the race. This was somewhat scary all the way through the half marathon but the guy kept chugging along.

Charlie Hoolihan

Charlie is the Director of Personal Training at Pelican Athletic Club in Mandeville, LA.

He has been coaching and personal training since 1971 and is a former LSU varsity swimmer and Hawaii Ironman finisher. He has also been a writer presenter and instructor at several national conferences for the National Strength and Conditioning Association, IDEA Fitness Association, American Swim Coaches Association and USA Triathlon. He has experience coaching all levels of client and athletes from stroke survivors learning how to walk again to collegiate runners, swimmers and soccer players.

Great article. Plenty of food for thought.

Can I ask the reason for the emphasis on weight training in the program?

Re the cycling: is the weight training before 5′ peak cycling effort to maximise mTORC1 levels in a short amount of time, and the 5′ peak cycling effort to then direct the growth towards the cycling specific muscles?

Was the 30-40′ cycling beforehand aerobic? If so, what was done to turn off AMPK before the weights?

Graham

It’s not quite as technical but you are correct in that the cycling component after the weights is designed to do some conversion of the strength training more directly to the cycling group.

HIT for endurance athletes is very new, individually based and has mostly anecdotal and coaching practice evidence rather than actual research.

The 30 – 40 min beforehand was aerobic Zone 1-2 and mostly to add some straight cycling time to his overall program.

My guess is your questions about mTor and AMPK is directed towards the interference effect. If so, there was little concern about the interference effect in that our primary goal was to enhance endurance rather than strength or hypertrophy.

The latter two due to interference of the mTor pathway seem to be the most compromised with concurrent training but even then, the evidence indicates it may not be as significant as previously thought. Currently there is no evidence indicating strength training interferes with AMPK pathways.

Hope this answers your questions. Feel free to reach me directly at Charlie@thepac.com