by Simon Wegerif

Who, why and what?

We have known for a long time that aerobic exercise increases heart rate variability (HRV) when performed regularly, but a new paper on a study performed by experienced French & Australian researchers, Chalencon et al., set out to look in more detail at the relationship between training load, performance and HRV. Importantly, they were trying to build a model that would allow elite swimmers’ performance to be predicted from training load and HRV (indicating both recovery and aerobic development). Data were gathered from the 10 swimmers weekly over a period of more than a year, including HRV measurements before performing a 400m time trial assessment.

What did they find?

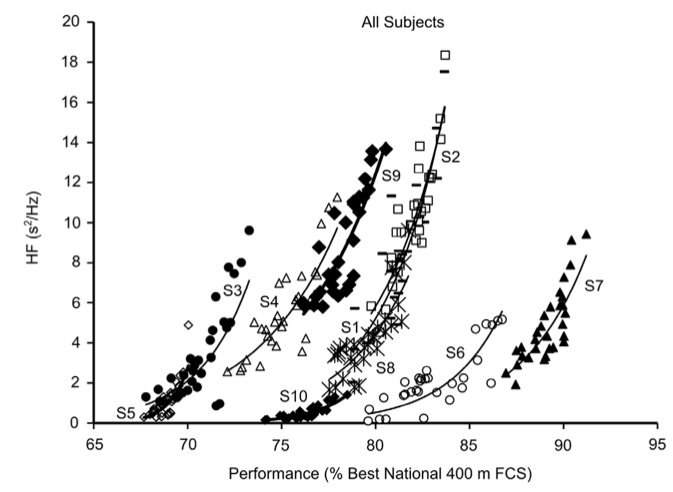

When individual HF HRV data were plotted against individual performance data, a highly significant relationship appeared for all of the 10 subjects, R² values ranged from 0.55 to 0.80 (p<0.001). This is shown graphically in the chart below:

In fact, the relation they found was so strong that they concluded using performance or HRV as the systems (model) output provided the same information on the impact of training on the fatigue and adaptation status of the athlete.

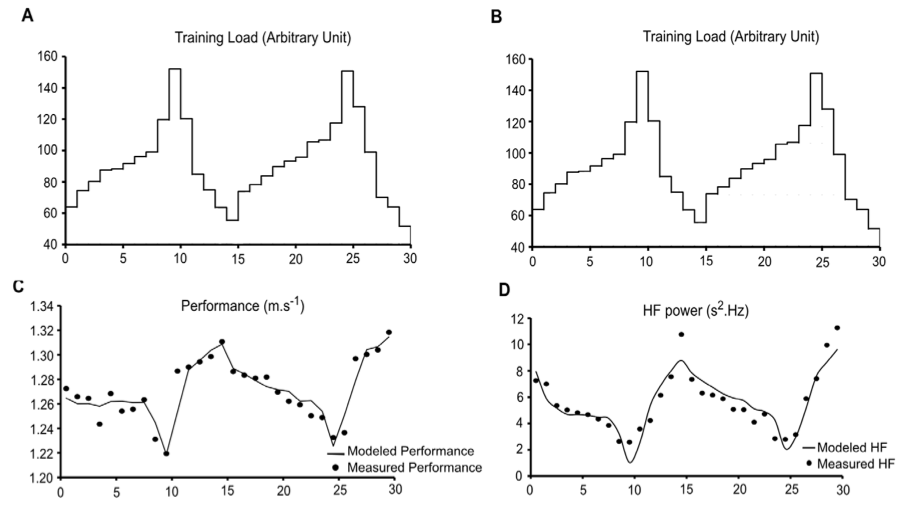

The effectiveness of the model can be seen in the chart below, where the training load chart over a 30 week period is repeated to allow comparison between the achieved performance, modelled performance, measured HRV and predicted HRV:

Layman lowdown

The conclusions I took from this study are:

Taper periods need to be quite long (2-3 weeks) in order for adaptations to really take hold. For an individual using ithlete to measure HRV, this could mean continuing the taper until no further rises in HRV are seen before starting to ramp up the next training block. Conversely, if HRV is not decreasing during an intensive training block – you’re not working hard enough.

There is no significant difference between genders in the model, implying that HRV based training is equally applicable for men and women.

It’s not the athlete with the highest HRV that wins, it’s the athlete that manages to increase their HRV the most that gets the biggest gains in performance.

Anyone can repeat this study for themselves by doing regular performance tests in their sport and seeing how well their daily (or baseline) HRV correlates. We’d be really interested in hearing from anyone that has done this!

Interesting article. My own experience since discovering ithlete in July 2012 is as follows;

I started cycling in May 2012 and really had no idea on training. A few months later and much research directed me to the Mafetone system, which coincided with discovering ithlete. During this period I was training on the road, hills, flats, declines. In August we had our second child, so invested in a turbo. I used this more than the road for obvious reasons, and implemented the MAF system, which in my case was a heart rate of 127. Over the course of the remaining year, my HRV value gradually declined to its lowest point in December. Since I started adding intervals and doing more road work in the last few weeks, I have started to see it rise again, towards the values I had in July. Proof I believe that riding at a steady pace without intervals does not necessarily improve fitness, whereas intervals either on the turbo or using a road route with climbs, does, as long as the heart rate is allowed to fall down to zone 2 on flats. Just my view

I have been using the iThlete regularly and I have found the HRV reading to increase during the taper period. Prior to the 2010 Bupa Great South run I steadily saw HRV readings increase to near maximum levels for me during the taper period. At the race I went through the 5 mile point 30 seconds faster than my 5 ml PB. I matched my 10K PB at the 10K point and then just fell outside my 10ml PB at the end. I was 53 and my 10ml PB was set when I was 40. My time of 56.42 ranked 6th fastest for a vet 50 in 2010. This was a post race observation and I knew before the race that I was feeling good. What would be better now is to have the HRV information in advance and know you are going to run well. That boost in confidence could well bring down the times a little further.

I have been using the ithlete from Jan 2012 to May 2012 building up for the Road and TT Age Group Nationals in NZ. Then I had a break until end of Nov 2012 and used it again since then to build up for a half iron men in Nov 2013. I like the ithlete (not sure why) and measure almost every morning but struggle to get really meaningful data out of it. For example, for the build up to the Nationals I progressively increased training load and intensity – and yet – my HRV had a trend upwards – the opposite to the study. (Maybe I didn’t train hard enough?).

This time around I use the Mafftone system very strictly and MAF performance goes up every MAF test in running and cycling. I hardly increased the training hours and not the intensity at all over the last two months. My HRV was pretty steady. However, I had my first all-out high intensity 25 km 5 days ago. After that my HRV jumped up almost 20%. I noticed that in the past. After a high intensity effort my HRV goes up and I would expect it to go down. Really confused to figure it out. Any ideas anyone?

One thing that does make sense though is that my HRV usually drops after bad/short sleep or drinking alcohol in the evening.

Markus. I think this proves what I stated. I think the MAFF method is great up to a point. Even Mark Allen believes that you need to add intervals in after a certain time just using MAFF, as it contributes to increased fitness. One thing is that the ithlete is great for showing when you need to add intervals in; if you are using MAFF and your HRV declines over 3 months like it did with me, in hindsight, if I had added intervals at some point then it would certainly have increased my HRV, which is the case now that i do include intervals. As soon as the ithlete gives me the Orange, I back down to MAFF again and let the interval work soak in, and let the HRV build upwards again. When it starts to decline again, then back to intervals. I believe doing this over the course of maybe a year or two, each time you go back down to MAFF, the HRV value is slightly higher than the last time you went back down to MAFF, hopefully, but only your data will show this. After a good deal of time your fitness level should be quite high, subject to genetics

Andrew – that sounds like a good recipe, and mirrors what I have learned about the training of elite endurance athletes, who under coach supervision polarise their training between high volumes of aerobic (MAFF) work and intense intervals that are chosen to represent the tough parts of their events. The mistake most recreational athletes (and even so pros) make is to assume that more intensity is always better, which quickly leads to staleness, and a perpetual state of incomplete recovery.

I also heard that Mark Allen alternated base building and switched to intensity when the gains stopped accruing, and back again when recovery was needed. I like the analogy of a diesel engine with a turbo – the aerobic work builds the ability to deliver power continuously at low revs, whilst the turbo adds horsepower at the top end.

I think you are right that correct periodisation should lead to an HRV baseline that climbs over the long term when compared during aerobic base building (MAFF) periods.

Thanks Simon. I am going to the trouble of having the XR-Genomics Predict+ test (http://www.xrgenomics.co.uk) to see where my genetics place me in terms of the fitness levels I can achieve. Once I have this feedback hopefully I can tailor my training more effectively between MAFF periods and interval periods