Can changes in HRV predict changes in running performance?

Buchheit et al.

Who, why and what?

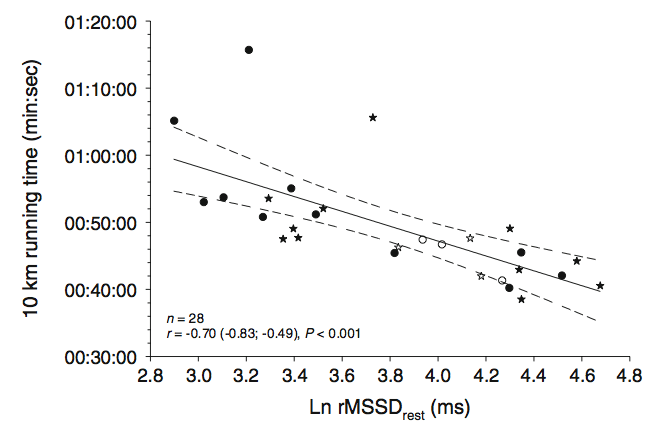

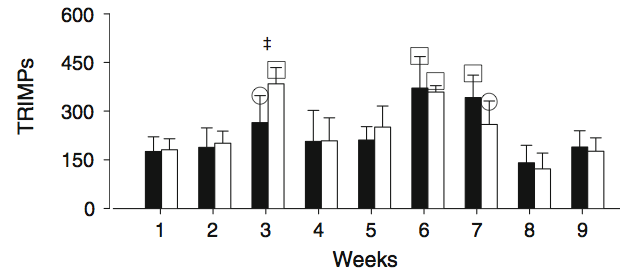

An experienced team of researchers, led by Dr Martin Buchheit (Aspire Academy), set out to assess relationships between running performance and heart rate variability (HRV). The assessment was conducted during an 8 week training program in moderately trained runners who had performed at least one 10k race in the previous year. 29 participants (average age 37) performed a 10k run before the supervised training program and then again at the end, after a short tapering period designed to maximise performance. HRV was monitored every morning using a Polar S810 to record RR heartbeat intervals, and processed to give parasympathetic HRV as LnRMSSD (which is the same measure as ithlete uses). They also measured heart rate recovery (HRR) after a standardised 5 minute exercise every second week during the training period.

What did they find?

- Out of the 29 runners who completed the training, HRV data was only complete in 14 cases due to artifacts and HRV recording problems.

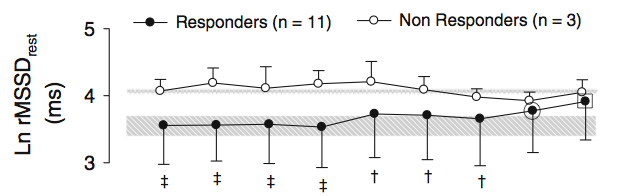

- Of these 14 with complete HRV data sets, 3 were considered ‘non-responders’ because their 10k run times did not improve after training.

- Participants with the highest starting HRV were the fastest runners, but those with lowest starting HRV showed the most improvement.

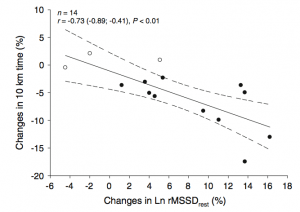

- All 11 responders showed increases in their morning HRV, and the ones with the largest gains in performance showed the biggest increases in HRV.

- An improvement of 10% in 10k run time required an average of 15% improvement in morning HRV, though two participants who achieved improvements of 15% in HRV achieved a more modest 3-4% improvement in 10k time.

- Morning HRV correlated well with HRV measured after the standardised 5 minute aerobic exercise, and (negatively) with heart rate recovery.

Layman’s’ Lowdown

If the findings of this study scale up to larger numbers, and across different endurance events, the conclusion is that if your HRV improves, so will your race performance. The converse being that if your HRV baseline does not improve during training or taper, neither will your performance on the big day!

Also, don’t be disheartened if you have a modest ithlete HRV score to start with – a good training program can result in significant improvement.

Implications for HRV guided training

The implications of this study I find far reaching, and even after re-reading the paper several times I still don’t think I have got everything out of it that I would like to. The finding that only those participants whose morning HRV increased showed improved race times is similar to the findings of Chalencon et al for swimmers (summary available here), and no less striking.

The challenge is to find individualised training programs that cause autonomic adaptations to take place. For sure the ratios of times spend in different intensity zones, as well as periodisation are important. In this latter aspect, it would be interesting to see whether a training program that produces beneficial adaptations during a period of 6-8 weeks continues to do so for longer periods, and whether the pattern of daily or weekly changes in HRV could be used to predict whether a particular program needs to be refreshed to keep the body guessing and avoid saturation (as well as the negative psychological effects of training monotony).

Another interesting aspect was the use of a standardised protocol for taking HRV measurements after 5 minutes of aerobic exercise. This could (and I believe is) being used in team sports where compliance with waking measurements might be an issue, so HRV tests can be performed supervised on players shortly after they arrive at the training centre, with the opportunity still to vary the day’s program depending on the results.

Thoughts on any of these aspects very welcome, as ever!

by Simon Wegerif

Great article Simon… I train at MAF and below and record every run and heart rate and there is definitely a link between hrv and speed at a particular effort.. sometimes my starting heart rate can be really low together with a low HRV and I set off thinking I’m going to have a pb for a giving heart rate and then my hr jumps up to above average so I bring down effort to remain below maf.. and vice versa.. Im also sure that vitD helps HRV score. with Vit d now being produced in Glasgow for the first time in 6 months I have high hopes for an increase. Also Simon that’s twice over ignored the don’t train even tho I had a big jump in HRV.. those 2 occasions were my best times but 2 days later on both occasions hrv plummets.!?

Leo,

have you read Simon’s articles on Polarized training? I trained exclusively at MAF for 3 months and my HRV gradually declined over that time, to its lowest point. It wasn’t until I started to introduce intervals in January that it started to climb again. Apart from a blip in March due to illness, I am now back up to where I was before MAF. The Polarized blog coincided with my own eventual beliefs on training. I think MAF only has its value, as long as the volume is high, and that was my problem, I just couldn’t get the volume of work in to make MAF only pay. But add in the small percentage of HIIT and the HRV score responds. BTW I am a recreational athlete, and get in about 7 to 9 hrs training a week

Hi Andrew,

I am surprised to hear that your HRV dropped doing MAF. My HRV climbed from doing MAF training steadily over the last four month from about 65 to 80. And I was only doing 6 – 8 h average training per week, split up into running, cycling and swimming. At the same time my race times improved. Same experience last year with about 10 h per week MAF training only cycling. Best form of my life. Are you sure you do the MAF training right?

Yes Markus I was training at MAF correctly, 132 bpm (180 minus my age of 48) it’s not that it is difficult to get right. Don’t get me wrong I am not knocking it. However, as Simon points out in this article, the challenge is to find individualised training programmes that cause autonomic adaptations to take place. In my case, and I stress my case, MAF was not as beneficial to me as it obviously was for you. I personally beleive that someone can’t expect to write a book or training programme that fits everyone. It might fit a certain percentage of those that follow it, but they can’t claim it will suit everyone who uses it, after all, these people are looking to earn money off it. I think the underlying principle of MAF is not to train at a high intensity on a regular basis, but to use it for a manageable percentage of your training programme and then revert back to lower intensity/aerobic training. Again this is individual. For me, using HIIT works, and this is reflected in my HRV score. Simon asked me to write a blog based on my results using this style of training, or the 80:20 polarised traing as it is known here; it is in the blog section of the ithlete web site. The results speak for themselves, in my case. I firmly beleive that each one of us has to try the different forms of training to see what works best for us, using HRV to confirm. Just to be clear, I use the 80:20 method for around 6 to 8 weeks leading up to an event, then the event itself, then back off to a less intense training programme until I feel right again. I beleive the event itself can take a few weeks or months to fully recover from. In my experience I have even taken 3 or 4 weeks off or aerobic training only and when returning back to proper training I have hit PB

Out of curiosity, I looked at data from the 4 times I cycled up the Col de Vence over July & August this summer, and looked to see what variables could best predict my change of times.

The result is clear to see – Daily HRV had a correlation (R squared) of 0.85, the next closest was the resting HR at 0.7 (standing, recorded at same time as HRV) and then HRR (HR recovery at the end of the effort). Interestingly there was no significant correlation between the achieved time (performance) and the average HR during the climb. Further tests of this kind should include accurate power measurements though.

Further evidence, adding to the research by Martin Buchheit, Chalencon, and recent comments by eg Zane Duquemin ‘I’ve been using @myithlete for 18mths and it correlates really well with throwing distances’ that daily HRV really can predict your performance with sometimes scary accuracy.

We’d be really interested to hear from anyone else who has similar experiences or data we can analyse.

Hello Simon,

I am a 51 year old statistician who has been interested in HRV research for years. After using Suunto for a long time I have started using Ithlete primarily due to it’s ease of collection and nice built in graphic capability. You might be interested in the way I am using your product. I find it important to take readings in both the supine and standing positions. It has been my experiance that the difference between these measures is the best HRV indicator of exercise readiness ( I believe there quite a bit of research that also supports this). I have detailed my approach here:

http://missingcomplement.blogspot.com/2014/04/a-method-for-monitoring-fitness-and.html

Thanks, I am finding Ithlete to be a very use marathon training guide.

Hi Seth

Thanks very much for the link & indeed your blog article which I find thought provoking. I’m currently part way through the Stanley paper & want to think about all the research conclusions before giving my view, but I’d be very happy to correspond via email or Skype in the meantime (simon@myithlete.com).

Best regards

Simon

Hi Simon,

Thanks for the reply. As I have continued collecting data I am coming to feel that even when taking HRV readings in both the resting and standing positions it is crucial to place the results in the context of both short term and long term training loads.

I have also seen some recent separate papers lead respectively by Plews, Bucheit, & Le Muer each with data supporting the use of weekly RMSSD averages (rather than daily values) in monitoring fitness change. I found the third paper especially enlightening:

‘Evidence of Parasympathetic Hyperactivity in Functionally Overreached Athletes’

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23657173

I know that higher HRV in standing position is generally associated with improved fitness. Yet the Le Muer paper showed the reverse effect on triathletes during an overload period. In this study the athletes that were put into a functionally over-reached (FOR) state increased their HRV (especially in the standing position) during the training overload period while their performance on fitness tests decreased. After a taper HRV for the FOR group decreased back towards previous levels while the group did very well on race day.

I am 3 weeks out from a marathon and just completed a simulation run on Saturday (18 miles with 16 at marathon pace). My standing HRV the day after (Sunday) this strenuous (intentionally slightly over-reaching) workout increased to it’s highest recovered level ( 73 only 6 points below resting supine of 79 on that day). Yet by the next day (Monday two days after workout) standing HRV had dropped to 58 while resting HRV was 82, and I felt mostly recovered. I interpret this as being in an FOR state temporarily after the tough workout on Saturday with a super-compensation effect showing up mostly in standing HRV.

On the other hand I think depending on the athletes initial condition and training load progression that Increased HRV often does correspond with improved fitness or exercise readiness. So while I am finding the tracking process fascinating and useful I think interpretation can be complex.

I have been exceedingly busy of late, but plan to update my post soon with an emphasis on weekly averages and also adding a sub-maximal fitness test to help interpret all the results.

Many thanks!

Hi Seth

Yes, the Le Meur paper is also an interesting one! I’ll share my notes which I am gathering with a future Research Summry in mind:

1. It’s a sophisticated, well conducted study that reports plenty of detail, but not in such a way as to become a confusing mass of data or paralysis by analysis

2. The parasympathetic dominance is a real, consistent effect in this group, which manifests first as a reduction in HR at the end of Wk 1 during the overload phase.

3. All independent measures are consistently saying the same thing (HR, LnRMSSD, Ln HF), and the effect sizes are slightly larger in the standing position and when taking 7 day averages as opposed to single day measures.*

4. Physiological explanations could come from both central & peripheral mechanisms, including SA node remodelling, Beta receptor sensitivity downgrading, and / or decreased catecholamine production, though I am puzzled as to how the latter two could occur without a period of elevated production preceding (which would be associated with elevated resting HR & decreased HRV)

5. Maximum HR during exercise is reduced whilst the PNS is dominant, but whether this is parasympathetic brake (Porges Polyvagal theory), adrenal fatigue / beta receptor downgrade or a ‘Central Governor’ effect I don’t know.

6. A 1wk taper was sufficient to largely reverse the OR effects & to show performance gains, so the classification must be FOR rather than NFOR.

7. This study is somewhat at odds with other sampled / programmed OT studies such as those by Uusittalo and Pichot, who demonstrated sympathetic dominance, which is often seen after isolated high intensity bouts (e.g. competition)

* I do have some views on this: Firstly, if studies are going to report daily HRV, it should be measured every day so that the mean, SD can be properly calculated from the population rather than a (non-random) sample. Secondly, I have seen much smaller CVs in daily HRV sent to me by endurance athletes than reported by Al Haddad et al, which I attribute to i) paced breathing at a comfortable rate, and ii) a high level of familiarity & therefore repeatability of the ithlete morning test. I also have a small pilot study paper in press that shows superior performance prediction from daily values compared to weekly averages in non-elite cyclists.

…and just to be clear – ithlete does include amber & red warnings for both acute & accumulated parasympathetic dominance (contrary to some reports elsewhere!)

Hi Simon,

I really appreciate your level of participation on the blog. I also agree that Ithlete has been very well designed, incorporating current research, and allowing ease of use while at the same time capturing the most essential data. In addition the graphs and dashboards provide the user with a great deal of flexibility in how they capture and track data, and the raw data can easily be upload as well. I think all this makes it’s use adaptable to new findings as they occur.

All your points are interesting and well taken (especially the point that if the cause were reduced beta receptor sensitivity and catecholamine production that it should have followed an elevated period). In my initial reading of the study in question I had thought they had taken daily HRV measurement’s as the basis for the mean weekly averages. I know they selected day 7 as the daily measure since that was the day of weekly fitness testing. I was wondering if they had looked for any relationship between daily HRV measures and previous day training loads as I had not seen that reported. I think I will take another look at the paper.

I am looking forward to the reading your pilot study results as they become available. It seems that recreational athletes should not be surprised by different HRV relationships to training as opposed to elites.

I think you all take too much out of this. Given the way how HRV as RMSDD is calculated, it is linearly dependent on the average HR. Imagine RMSDD = 1/HR×€, where € is a stochastic funtion with avg 1 and a certain standard deviation. Typically the better someones condition, the lower his/her resting HR. In my own case, my resting HR correlates almost one to one with my ten k time. Hence 10-k time ~ HR. Given the formula above, this means 10-k time ~ 1/RMSDD. No magic. Just how the HRV is calculated.

Regards,

Barry

Hi Barry,

Thanks for the comment. When starting to study HRV in 2008 both from theoretical perspective, as well as performing research on myself, I had to be convinced that HRV was not just reflecting 1/HR before developing ithlete, otherwise we could rely on resting HR as you rightly point out.

Papers like this one by Bernstein (91) http://psychology.uchicago.edu/people/faculty/cacioppo/jtcreprints/bcq91.pdf present evidence of simultaneous activation & inhibition of both ANS branches, and empirically we see a distribution of daily points on the ithlete Pro training guide away from the top left – bottom right which you would expect if all ANS behaviour was reciprocal.

I do agree with your point about decreases in resting HR over time signalling improved fitness, and there are formulas you can use to predict VO2 max that use this eg VO2 max = HRmax/HRrest x 15.2

Simon,

I do believe there is info in the hrv data, given that it is affected by the previous training sessions. However I do wonder if the RMSSD should be divided by the average RR of the total series or the average of the points from which the differences are taken to get a dimensionless number and get rid of the dependence of the outcome on the hr.

Regards,

B

Hi Barry

Good point. Some Finnish researchers proposed something similar a few years ago – normalising with HR for both RMSSD & HF power, but it hasn’t caught on in the wider community. I would argue that the ithlete Pro Training Guide does allow separation of the two since they are plotted relative to 30d averages in a 2-D space using Z-scoring.

Best

Simon

What I like about Ithlete is that it’s valuable to ordinary non-professional athletes like myself. It has been invaluable in guiding my training after major spinal surgery. Even I have found an undeniable correlation between my Hrv and my physical strength. I could not manage without my daily reading. It has become indispensable.