As some readers will remember, two years ago I prepared for the Mallorca 312, the longest (and possibly best organised) Gran Fondo cyclosportive event in Europe. Last weekend was the third time I have done it, and my target was to beat the previous two years’ times. My training volumes & intensities were very similar to previous years, and I was using the same bike, although I had a new Dura-Ace power meter fitted to my bike. I used Best Bike Split to give me target power levels, useful especially for the longer climbs.

What I really wanted to focus on was nutrition & hydration, which had been sadly neglected the previous year, and which led to me crawling past the finish line in a very uncomfortable state, feeling nauseous for hours afterwards. So what did I do differently? This time I recognised that however much it seemed like a good plan, it was unlikely I would be able to force down solid food after about 6 hrs. I remembered from the previous years that SiS gels still tasted acceptably ok after that point, and that plain water (not the event supplied sports drink) would probably go down in small sips at a time. Taking a tip from an Ironman triathlete buddy, I emptied the contents of 10 SiS gels into a Torq recovery bottle, which has a one way valve suitable for thick liquids to pass through. SiS gels are also isotonic, so you don’t have to wash them down with water if you don’t want to. I also ordered a new 950 mL water bottle, both for the capacity and also because it would be uncontaminated by the taste of previous sports drinks. For the first 6 hrs, I would aim to eat 60-70g / hr of carbs from flapjack bars, dried fruit, and jelly beans. Yum!

So how did it go? As for previous years, we arrived on the start line nice & early so we could join the motor paced fast group & get a free ride to the base of the Col de Femenia. That worked out fine again and I settled into my target power range of 195 – 210W, which really didn’t feel like much effort at that point. The weather, roads & scenery were superb, and the first 5 hrs passed quickly, with all eating & drinking going to plan. After the mountains, I was lucky enough to join a group of Mallorcan riders who rode smoothly at a perfect pace. Great I thought – just have to hang with these guys for a new personal record time! Unfortunately, this plan came to an abrupt end when, on passing through a village which had a feed station, our new friends all dismounted & went into a restaurant for lunch.

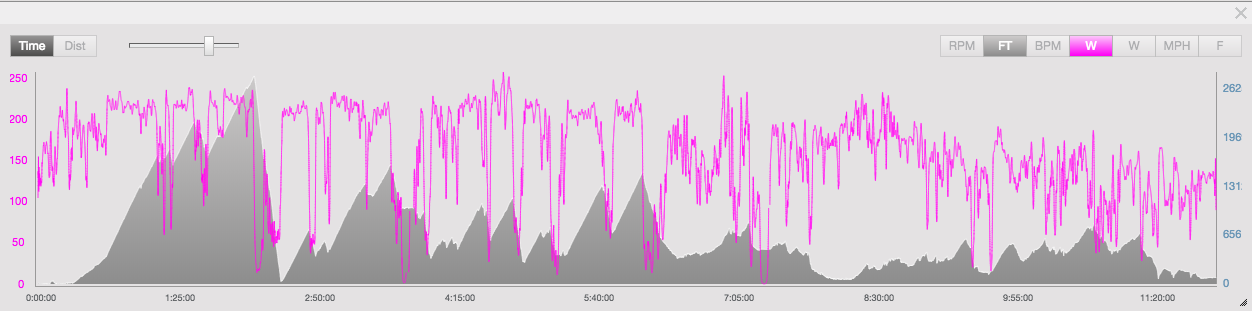

It was now time to switch to the gel + water strategy, but that coincided with joining a group that was not as well organised, and put in 300W surges over every little rise. The bad thing about that is that intense anaerobic activity relies heavily on carbs, at the time when I was having a reduced intake forced upon me by the guts starting to switch off. The outcome was inevitable – at 9 hrs I blew up and commenced the long, lonely, 2.5 hr slog for home. In the end, my time wasn’t too bad, and was within 1 minute of the Best Bike Split prediction at 11:42. Not good enough to beat the previous year’s 11:27 though. I don’t know what the answer is to maintaining energy after 8 hrs of riding – one person suggested electrolyte tablets as a way to avoid nausea. I do think I should have avoided the big carb consuming surges, but it’s very tempting to stay with a group both for company as well as energy savings from drafting. The power profile from TrainingPeaks is shown below. You can see that intensity discipline was well maintained until about 6.5 hrs, when the spikes started to creep in:

The route I took is also available as a one minute video simulation by Relive – a great fun app that connects to Strava in case you haven’t come across it.

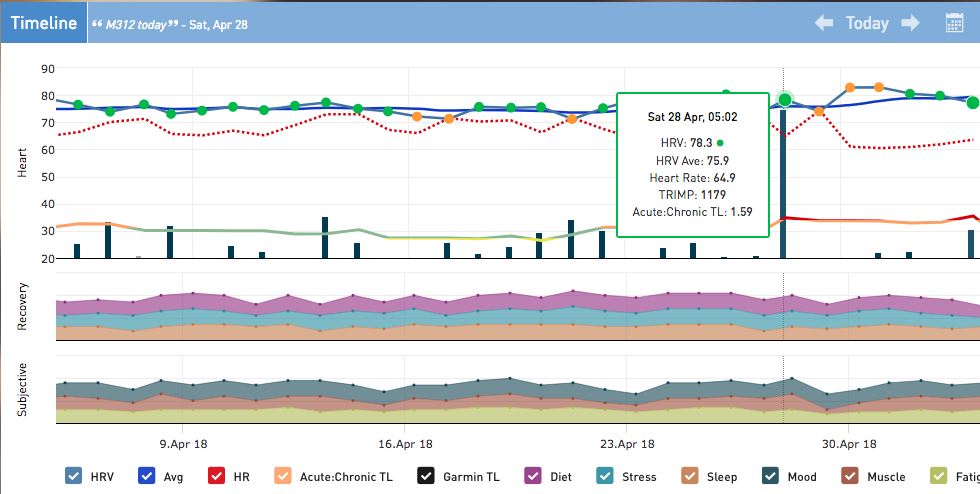

On now to the recovery. This year, I did not collapse at the finish line, and I actually felt like eating dinner, so that was definitely an improvement. The image from ithlete Pro shows how my HRV changed over the next few days after the event.

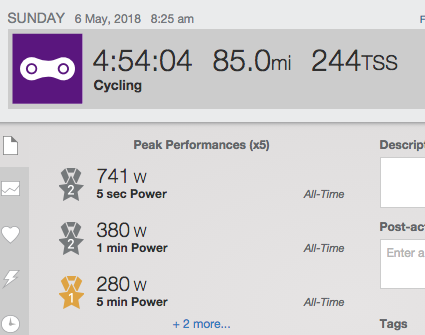

On the Sunday, I had a low HRV / high HR amber, which was expected, and very sore legs! Monday & Tuesday are interesting, because they are unusually high HRV scores, well above my baseline (blue line) and carry an amber warning. These coincided with a lower than normal resting heart rate, and a lot of physical & mental tiredness. By Weds & Thurs (4-5 days post event), things are getting back to normal, in the green, but with a raised HRV baseline. A raised HRV baseline often corresponds with improved aerobic fitness, and this weekend, a week after the event, I have had some all time power records in TrainingPeaks:

A final point I want to make about the HRV chart is that a criticism sometimes levelled at HRV is that daily readings carry high variation and therefore can’t be trusted. In my experience, this is almost always down to the measurement conditions & protocol. You do need to be disciplined with taking the reading at the same time every day, breathing in a controlled manner (in through the nose – out through the mouth) and using a validated sensor (I use the ithlete finger sensor). We did an article for TrainingPeaks recently which highlighted common misconceptions & best practice for taking HRV measures to ensure they are as reliable and insightful as they can be.

From endurance, I now need to get my body ready for out & out racing at the Tour of Cambridgeshire in 3 weeks time!

By Simon Wegerif.

Hi Simon,

That’s an I nteresting analysis. I am surprised that you think it was the nutrition that caused the blow-out? From your narrative and with my coach hat on I would be questioning your pacing. The key comment for me is that when you joined the group that seemed to you disorganised your race unravelled.

I think you follow a high fat/low carb diet? So you are fat burning and your training will have developed a limiting burn rate for you. I would expect you to hit a wall when you get off your viable pace. You can’t really add significantly to your fat stores during a race.

You chose to focus on nutrition this time and I suspect you got that right but got distracted from your pace by the odd group you joined?

Hi Martin. Thanks for the comment. There has to be a pace / fuel mismatch, but I don’t know what was the limiting factor at this point. I did try to ingest enough carbs, and perhaps a telling observation is that after 8+ hrs, carbs no longer seemed to have the rapid reviving effect I have seen on shorter events & races. That would tend towards your view that I simply ‘burned all the high intensity matches in the box’, and that was it!

I think I need to better understand the Critical Power concept https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-017-0688-0 and pay very careful attention to the amount of time spent above 2nd lactate threshold. Another Coach friend advised me to set an absolute power limit that I would not go above under any circumstances, and I should try to work out what this is for me over that distance.

Simon, I agree with your other coach friend. I work on the theory that you can only adjust your viable race pace in training. In a race, a shot of carbs might help (physiologically and psychologically) for a quick burst but over a long 8 hour session I would expect early carb ingestion to cause you problems later. Why would you eat carbs early on a long race day? You can’t really store them as usable fats and if you are not careful you will disrupt your body’s natural fat-burn process. I think you are on the right track with understanding and developing through training your viable maximum race pace and focusing on that alone on race day. The tricky bit is ignoring what others are doing but I think you have to do that. In endurance events other competitors are only relevant to you if you can steal some slipstream without disrupting your own pace and then at the end of the race where you can adopt a sprinter’s mentality (if you have anything left).

Thanks Martin – those are all good points. I would like to be able to extrapolate from shorter sessions, as it’s not realistic to ride different paces (inc surges with slipstream benefit) and fuelling strategies for 9 hrs in training just to see what will happen. I wonder if new software like that from Xert http://baronbiosys.com/understanding-mpa/ will be able to help in future.

Simon, thanks for the links. I guess you are asking yourself two questions; how can I train most effectively for a 9 hour race and how can I know (other than how I feel) when to push and when to ease up? On the former I am interested in breaking down the different elements of the race and developing both technique and power for each element. It means finding a balance for each individual based on where you want to race (from out-and-out sprinter to Ironman endurance) and building each block over a long period (because it takes time and as you develop each element your technique will change/have to change). If this works (so far it has with my sprinter) then you radically reduce the duration and length of training load, which allows better recovery and maintained higher quality health during recovery (instead of training for so long that you have to recover fitness while health is sub-optimal). We almost never use race distances during training. I think it dulls performance and gets you believing things that you would be better off (as a racer) not knowing. Leaving aside the scientific interest and time trialling, why do you need to know before a race what your exact strategy should be if riding solo? For a team you can control strategy to an extent but as an individual you are reacting to either the race or your own feeling. For your training I would isolate the elements of cruising at different speeds (below MAF level) to build your endurance base (which also builds speed possible at cruising levels). Then devise a series of drills where you first calibrate your performance by sprinting and/or climbing at different intensities and durations up to about 15 minutes max. Once calibrated you could then drill to improve performance. This will also (over time) give you a pretty reliable sense of how long and how hard you can push when a push is either necessary or valuable for race performance. Looking at the MAP thing I think it’s interesting that the aim seems to be to be able to put numbers to race performance. It’s akin to an F1 car being finely adjusted and tweaked outside of the driver’s seat. Even in an F1 car the fuelling goes wrong at times because conditions are never entirely predictable in terms of weather, safety cars etc. The big difference is that F1 entails all of the cars working on the same basis so that if a certain race is more punishing on fuel, it will generally be so across the board and all will adjust in a somewhat similar way. Cyclists are all different (from each other and perform differently in different circumstances) so on the day that I am using more fuel you might be storing yours well etc. The detailed monitoring will only help in a race if all the racers are using them and even then some riders will just be having better days?

Thanks again Martin. Certainly some food for thought in there (pun half intended). In a way I wish there were a human physiological equivalent of the F1 fuel gauge with sophisticated algorithms that could tell me how much longer I could keep going at different pacing scenarios. Even just “You can only hang with this group for another 10 minutes before going back to MAF” would be quite helpful. I recently read Alex Hutchinson’s new book ‘Endure’ which really focusses on the effect of the mind being the ultimate endurance limiter. Unfortunately though I am quite good at ‘digging deep’ and don’t think the mental side is limiting me (I could not manage a finishing sprint or even flurry for that matter in Mallorca). Best Bike Split did predict my total time accurately, although I did not follow its pacing recommendations later on. The only physiological metric it uses is FTP, and there is plenty of information out there as to how to improve that, though I have to think that for longer events, power at MAF must also be important, and may not be a fixed % of FTP.

;). Well you are the science guy so you are bound to want to analyse the life out your race. I am an engineer designer so I come from the other direction; work out the result you want and design your way to it. We use the science to enable the design not as a replacement for design.

I will have a read of ‘Endure’. Your mental strength at digging deep suggests to me that you might gain from working on ‘not digging deep’ because that is your default and that’s why you blow out. Instead of using your mental strength to discipline your pacing you are digging deep and that’s wrecking your pacing. You endurance athletes tend to dig deep when you should be lifting your head up and checking that you are on the plan.

I like the fact that reading the above you have said that you didn’t stick to your pacing plan and you did stick to your nutrition plan but then blamed your blow-out on the nutrition. My athlete has a sign on her wall which says “stick to the plan”.

We should meet for a chat one day…

Thanks Martin. I suspect my other Coach friend will also say ‘stick to the plan’, and do let me know if you are ever down in the Southampton area.